This topic has always been ghoulishly interesting to me. Well, maybe not always. But for a while now at least.

Trepanning (or trephining) is probably not a totally unfamiliar word? For me, it tends to conjure up images of primitive, straggly-haired (or possibly tonsured, for easy access) people wearing skins and scratchy shirts gathered around smoking fires with rusty implements, gouging each others' brains out. However, as with most things, it's a bit more complex than my vivid imagination depicts.

I'm not entirely erroneous, though...in fact, the drilling of burr holes is the earliest known surgical procedure, so the skins and shirts may not be too far off. (If it seems surprising that poking holes in the skull was the first doctoring that ancient man decided to attempt, keep in mind that soft tissue doesn't survive so long as bones.) Neolithic archaeology indicates this brutal procedure was not uncommon. And brutal it must have been, with nothing but weakly fermented alcohol to dull the pain of drilling through scalp and skull; however, if we're going to be logical (and we're going to return to the above illustration), rusty it wouldn't have been - it seems that stone and bone tools shaped like pointed teeth were the surgical implements of the day.

It also seems that the procedure wasn't lethal - or at least, that it didn't spell death. Analysis of skulls that underwent trepanning reveal bone growth, indicating that a fair number evaded infection, hemorrhaging, and excessive brain damage to live out the remainder of their lives. Indeed, the positive effects of trepanning made the procedure persist not only through time but also across continents. Prehistoric Germanic and Celtic tribes may (arguably) have started the practice, but holy skulls have been found in South America, and even farther afield. (Although, as an archaeologist, it's important to attempt to distinguish patients of trepanning - both successful and not - from victims of post-mortem modification, a.k.a. heads on pikes.)

Although, as anyone will tell you, morbidity is not efficacy. So why would anyone risk a hole in the head in an age without antibiotics and the rest of modern medicine? Cave paintings, Greek texts, and

medieval, and Rennaissance documents provide a slew of answers to this question. There's some evidence of religious sects using burr holes as part of ritual and tradition, but more medical reasons appear to be the prevailing rationale for trephination. Epileptic fits, migraine, and the broad category of 'mental disorder' number among the most common. ...Incidentally, this in itself is quite interesting; for much of human history, the brain, with its fluid-filled ventricles, has been considered nothing much more than a pump. Nowadays we accept the concept of the brain as the seat of consciousness, but it hasn't always been so.

One further reason for trepanning is, of course, head injury. Just as today an ER doctor will bore a burr hole in a thumbnail that has been smashed by a hammer, in days gone by, field surgeons on the battlefield would treat severe head trauma from maces, swords, etc. with a bit of light trepannation.

I do still have some questions...or at least one question...which is, I can't figure out how, in pre-modern times, the surgery was completed. Was the hole cauterized and left open to the air? This seems unlikely...was the skin flap sewn back over the top? In Master and Commander, the opening is filled with a coin...was it standard procedure to use a bit of metal? How did it not fall off? Was it wired on? But perhaps that's not something that intrigues other people.

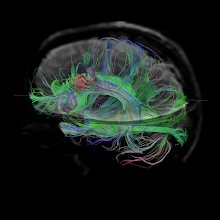

Anyway, speaking of emergency rooms, trepanning isn't one of those antiquated pseudosciences that can be consigned to the past. It's still used today in much the same way that it was in my last example: in extreme cases of epidural and subdural hematomas so that blood from damaged tissues or ruptured vessels can safely drain and not exert dangerous pressure on the brain. This, by the way, is known as craniotomy if the bone is replaced after the procedure and a craniectomy if not. Cranial burr holes are also used as an access point for brain surgery. This is, of course, commonly done under general anesthesia, but occasionally neurosurgeons will choose only local anesthetic. Ironically, the brain itself has no sensory nerves and so cannot feel pain; only the exterior tissues have these receptors. For these types of surgeries, a patient will need to be awake and alert during surgery during cortical mapping so that the surgeon can ascertain what tissues are most vital. Tumors in the temporal lobe, for instance, frequently associated with epilepsy (so perhaps the ancients weren't so far wrong..?) are often treated in this way.

That's not to say trepanning needs to make a comeback. It's a technique that should certainly not be abused (like lobotomy), and can in certain cases remain a pseudoscience (like phrenology). Modern-day cults and sects have occasionally advocated the procedure to increase blood flow to the brain, enhance activity and productivity, decrease fatigue and depression, or allow for heightened religious consciousness and awareness. And while I've taken cultural anthropology of medicine and am willing to live and let live when it comes to strange medical practices...if I ever get unhappy, I feel I'd need trepanning like...well, like a hole in the head.

Wednesday, June 2, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Ewwwww. Flaps of skin are nasty. And holey skulls!?

Post a Comment